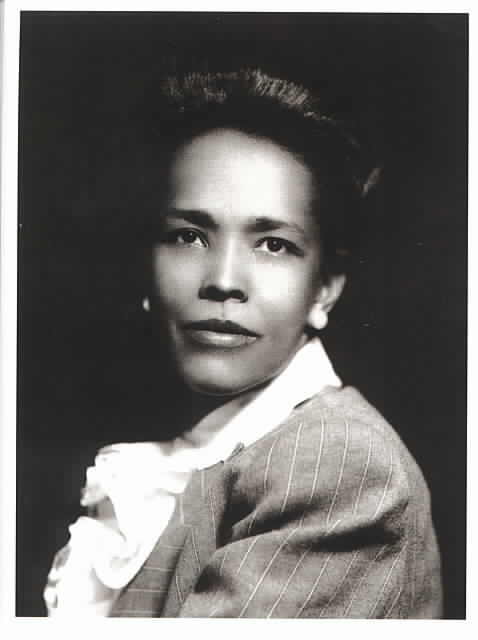

Maria Mitchell is best known for being the first professional female astronomer in the United States. She discovered a new comet in 1847 that became known as "Miss Mitchell's Comet."

“We especially need imagination in science. It is not all mathematics, nor all logic, but it is somewhat beauty and poetry.”

—Maria Mitchell

Maria Mitchell was born on August 1, 1818, in Nantucket, Massachusetts. She studied astronomy on her own time with the support of her father. In 1847, Mitchell discovered a new comet, which became known as "Miss Mitchell's Comet," gaining her recognition in astronomy circles. She went on to become a professor of astronomy at Vassar College in New York, tracking and taking photos of sunspots with her students.

Astronomer and educator Maria Mitchell was born one of nine children to Quaker parents William and Lydia Mitchell on August 1, 1818, in Nantucket, Massachusetts, where was raised and received her early education.

Mitchell's father, recognizing her interest in the heavens at an early age, encouraged her interest in astronomy and taught her how to use a telescope. She worked as the first librarian at the Nantucket Atheneum library from 1836 to 1856, all the while still gazing at the sky at night, studying solar eclipses, the stars, Jupiter and Saturn.

On October 1, 1847, a 28-year-old Mitchell, while scanning the skies with her telescope atop the roof of her father's place of business, the Pacific National Bank on Main Street in Nantucket, discovered what she was sure was a comet. It turned out that she was right, and that what she had spotted was in fact a new comet, previously uncharted by scientists. The celestial object subsequently became known as "Miss Mitchell's Comet," with the formal title of C/1847 T1.

In recognition of her important discovery, Mitchell was presented with a gold medal by Frederick VI, king of Denmark, who had an amateur interest in astronomy himself. Consequently, Mitchell became the first professional female astronomer in the United States.

The breakthrough brought Mitchell respect and recognition among astronomers and other scientists, and in 1848, she became the first woman to be named to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. The following year, Mitchell made computations for the American Ephemeris and Nautical Almanac. In 1850, she was elected to the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

In 1856, Mitchell left the Atheneum to travel the United States and abroad, and in 1865, she took a job as professor of astronomy at Vassar College in upstate New York, where she quickly became a well-liked and respected educator. Among many projects, Mitchell and her students continuously tracked and photographed sunspots. In 1882, they documented Venus traversing the sun—one of the rarest planetary alignments known to man, occuring only eight times between 1608 and 2012.

Mitchell was elected to the American Philosophical Society in 1869. Four years later, in 1873, she co-founded the Association for the Advancement of Women, serving as the organization's president for the next three years.

According to the National Women's History Museum, Mitchell once stated, "We especially need imagination in science. It is not all mathematics, nor all logic, but it is somewhat beauty and poetry."

In 1861, after her mother died, Mitchell moved to Lynn, Massachusetts, with her father. In ill health, she retired from teaching at Vassar in 1888, and died on June 28, 1889. She is buried with family members at Prospect Hill Cemetery in Nantucket.

In honor of the first female astronomer, the observatory in Nantucket was named the Maria Mitchell Observatory. Additionally, the Maria Mitchell Association, also in Nantucket; a World War II ship, the SS Maria Mitchell; and a crater on the moon ("Mitchell's Crater") were named after her.

Mitchell was posthumously inducted into the National Women's Hall of Fame in 1994.